Tuesday, 19 April 2011

From SLAKE: The Los Angeles Quarterly:

By John Albert

The first time I hear Van Halen I am fourteen years old, riding in a car through the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains. My friend Steve Darrow is riding shotgun while his dad steers the dusty old Volvo station wagon. Chris Darrow is in his forties and has long hair and a slightly drooping cowboy mustache. In the sixties and early seventies, as a member of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band and an obscure but influential group called the Kaleidoscope, he, along with Gram Parsons, Linda Ronstadt, and others, forged what became the classic California sound. His long-haired, Black Sabbath–loving son, Steve, sitting shotgun next to him, would go on to play in an early version of Guns N’ Roses. But on this particular night Chris is driving us and another friend named Peter home from a party thrown by a local ceramics artist. While the aging hippies and college professors sipped wine and purchased meticulously decorated casserole plates, my friends and I hiked into a nearby orange grove to smoke pot in the moonlight. And as the car heads home along Baseline Boulevard, passing the silhouttes of orange groves and vineyards, the three of us are still incredibly stoned and no one is talking much.

Someone turns on the radio. It’s tuned to KROQ, a small, independent station that has little in common with the corporate behemoth it would become. In 1978, the station broadcasts a strange mix of surreal sketch comedy and new music across the Southland. A show called The Hollywood Night Shift riffs on “barbecue bat burgers” and “downhill screen-door races.” Meanwhile, the station’s present-day last man standing, Rodney Bingenheimer, who morning goons Kevin and Bean use as a prop for their moronic shtick, introduces punk music to kids across Southern California. By this time, my friends and I have already fallen under the sway of the raw, new sounds emerging from a ripped, torn, and safety-pin-adorned England.

As we cruise along Baseline, I have no idea what’s on the radio. I stare out the window into a passing darkness with hazy, Mexican-weed-induced tunnel vision. Then, suddenly, this extraordinary sound from the car’s stereo snaps me back. Steve reaches over and turns up the volume. It’s guitar playing, but not like anything we have heard before. Until this very moment, the reigning guitar heroes have been English, amateur warlocks, such as Jimmy Page and Ritchie Blackmore, playing sped-up, bastardized versions of American blues. But this is faster and weirder. Toward the one-minute mark, the playing veers into completely uncharted territory, and the final forty-two seconds sound like Gypsy jazz legend Django Reinhardt on CIA acid.

It is a style of playing that will so dramatically alter the musical landscape that thirty years later it will sound normal, even rote. But in 1978, this burst of unabashed virtuosity and noise, something we’ll later learn is appropriately called “Eruption,” earns unexpected respect from three punk rock children and one middle-aged country rock musician. As the whole thing reaches a frenzied crescendo of undulating distortion, the four of us start to laugh.

Until, that is, the distortion immediately segues to a revamped version of the Kinks’ classic “You Really Got Me,” rumbling through the car’s little speakers. This is not hard rock as we know it—no highpitched, operatic wailing about sorcery or Viking lore. With no visual reference to go on, it seems to have as much in common with early punk as with bands such as Led Zeppelin and Rush—except, of course, for the crazy, outer-space guitar solo. In retrospect, this makes perfect sense. Before it became one of the biggest bands in the world, Van Halen routinely played on bills with prepunk bands like the Runaways, the Mumps, and the Dogs.

When the song ends, Steve’s dad, who may or may not be stoned as well, just nods his head and says, “Far out.”

***

It is the soundtrack to a world that doesn’t exist anymore. I know because that world is where I come from.

Van Halen had been playing the suburbs east of Los Angeles for several years before we heard them on the radio that night. In fact, the previous year, Peter’s diminutive, science-teacher mom, who when speaking tended to coo pleasantly like a pigeon, unwittingly supplied Van Halen with several bottles of bourbon and tequila. The occasion was the band’s appearance at a show on the local college radio station hosted by Peter’s older, but still underage, brother and some of his friends. Following seventies rock etiquette, they felt it only proper to provide the band with alcohol and other recreational substances.

I remember this because my friends and I had been coerced into distributing fliers announcing the band’s appearance on the show. Most of our peers glanced at the crudely rendered image of a young David Lee Roth flaunting his soon-to-be legendary chest pelt and bulging package and simply tossed the fliers away. A lot of those same kids would, several years later, pay large sums of money to see the band headline the massive Forum in Inglewood.

In the years leading up to their record deal and worldwide fame, the Internet was still science fiction and the only video game widely available, Pong, mimicked pingpong only without the riveting excitement and health benefits. As a result, kids were primarily focused on two things, rock music and getting wasted. Days were spent under the sun and smog, getting high, playing sports, skateboarding in empty swimming pools and on downhill streets. Weekend nights were devoted almost entirely to massive backyard parties. And Van Halen ruled the backyard party scene in and around the San Gabriel Valley.

Unsuspecting parents would leave town and hundreds of kids would descend on a designated home like tanned, stoned locusts. Down the block from my parents’ house was a large, ramshackle manor known as the Resort. Sunburned British drunks lived there, and their kids were a wild and eccentric brood bearing names such as Yo-Yo, Kiddy, Sissy, Lad, and Mims.

Parties at the Resort were notorious. I remember watching a formally attired adult couple slow their car in front of the Resort as a party raged inside. Some longhaired kids staggered into the street, walked onto the hood of the couple’s car and then its roof, howling like wolves. My preteen friends and I finally mustered the courage to venture inside one of the parties. There, we discovered a maze of hedonistic delights: the dining-room table lined with cocaine, a cracked door revealing a nubile high school girl having sex, people jumping from second-story windows into the pool, fights and noisy drag races in the street out front. Throughout the beautifully raucous affair, a young rock ’n’ roll band named China White stood precariously close to the swimming pool playing with all the swagger of the Rolling Stones at Madison Square Garden.

While Van Halen played the huge outdoor parties and lucrative high school dances, China White was the band of choice in my immediate neighborhood. The group was composed of young heroin addicts who wore cowboy hats and played Southern rock. Somehow, it was a style that made perfect sense in the slowed-down, drugged-out seventies suburbs. Besides a few performances at the Resort, the band’s highest-profile gigs were at the palatial hillside estate of a local ice cream fortune heir. The band’s leader, John Dooley, now lives in Bangkok, where he teaches music and plays in a rhythm and blues revue.

“Those were some epic fucking parties,” Dooley says when I reach him by phone in Bangkok. “We had a big stage on the tennis courts and the pool house was our backstage area. We invited 500 fellow students, charged a cover, and then got all my older brother’s biker buddies to bounce and run screen for the cops. There would be close to a thousand kids there and we would be getting high and fucking chicks in the pool house between sets. I remember we left with our guitar cases stuffed with cash.”

But it was with his next band, Mac Pinch, that Dooley’s path began to cross regularly with Van Halen’s as the two bands shared bills both locally and in Hollywood. “I was always really impressed by Eddie Van Halen and their bass player [Michael Anthony]. They definitely stood out musically, especially Eddie,” Dooley says. “Their singer, Roth, was like the guy we had—by no means a great singer, but really loud and worked the crowd well. They used to have a party van with the Van Halen logo painted on the sides, and Roth was always out there in that van. He was kind of obnoxious, but he had a real knack with the ladies. He would bring them out to that van one after another. I had more than my share, but Roth did better than his band and ours combined. We used to play this biker bar in Downey with them called the Downey Outhouse, where they served popcorn in bedpans and beer in urinals.

“It got pretty competitive between the bands, and one time our roadie unplugged Van Halen during a show at the Pasadena Civic.”

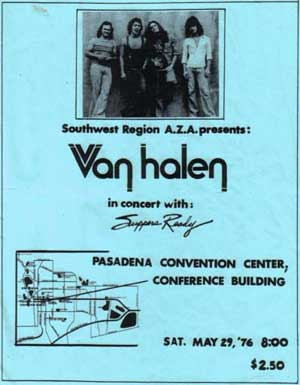

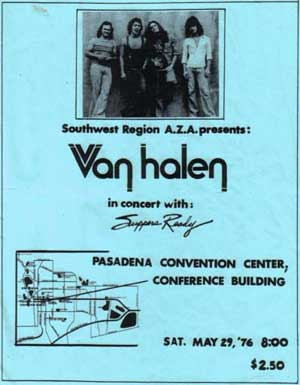

During these years, roughly 1974 to 1976, Van Halen surpassed all rivals, including San Fernando Valley stars Quiet Riot, to emerge as the premier hard-rock act in Los Angeles. Besides a willingness to play nearly anywhere at any time—the band once played an early-morning breakfast concert at my high school a few years before I attended—the band’s rise seemed due, largely, to two distinct qualities. One was the playing of Eddie Van Halen, who had perfected the innovative method of using the fingers of his picking hand to pound the guitar’s fret board, creating a lightning-fast, quasiclassical style that quickly became the talk of Southland musicians. Van Halen reportedly became so guarded about this technique that he began to play solos with his back to the audience.

And while the teenage boys came to marvel at Eddie’s technical virtuosity, the girls flocked to see the band’s flamboyant lead singer. David Lee Roth would take the stage shirtless, wearing skin-tight spandex pants or fur-lined assless chaps, none of which dampened his enthusiasm for jumping into the air and doing karate kicks and splits. Visually, Roth resembled a stoner superhero with his wild, long blond hair, muscular physique and exaggerated party bravado. But what set him apart from so many aspiring front men of the time, was that, unbeknownst to his mostly blond-haired, blue-eyed audience, Roth was Jewish. And though his father was a wealthy ophthalmologist, young Roth went to public schools and ended up attending primarily black John Muir High in Pasadena. As a result, he was able to merge an over-the-top, borscht-belt-like showmanship with the booty-shaking sex appeal of his Funkadelicized classmates. It was a combination that made Roth a near perfect rock star for those hedonistic times.

While Van Halen’s star rose, my friend Dooley and Mac Pinch were on a different trajectory. Instead of showcasing alongside their one-time rivals at Hollywood clubs such as the Starwood and the Whisky, the drug-addled young cowboys started booking USO tours and playing military bases to support their various nonmusical habits. When Van Halen finally had its big breakthrough and signed to Warner Bros. Records, Mac Pinch was off playing to halls of drunken Marines.

“Those were serious smack days for me,” Dooley reflects. “Eventually it all caught up to me and I had to come back home and do some jail time, and that was the end of the band.” (We don’t discuss how Dooley stole my parents’ television set.) I ask him if he has regrets after seeing his former rivals go on to such massive success.

“Do I think we should have tried harder? That maybe it could have been us?” he offers. “Sure. But we had a lot of fun playing those parties. I have some great memories. It was a pretty awesome time to be young and playing in a rock ’n’ roll band.”

***

Two years after first hearing Van Halen on the car radio, the world around me seems a dramatically different place. My once-long hair is now short and jagged and I’m wearing studded wristbands with a spider-shaped earring punched through an infected hole in my ear. In suburbs across Southern California, punk rockers have swelled from a besieged minority to an increasingly aggressive subculture. There are pervasive hostilities between the heavy-metal-loving “stoners” and the new punks. Both sides instigate violence. By now, I have been expelled from the local high school for truancy and am enrolled in something called Claremont Collegiate Academy. Despite its snooty name, the place is filled with kids who have failed at the local high schools. My classmates are mainly longhaired drug users, agitated Iranian immigrants, and kids with assorted behavioral disorders. The principal will eventually be arrested on child porn charges.

During one lunch break, I stroll out into the school parking lot and am greeted by the pounding, tribal drums of Van Halen’s latest single, “Everybody Wants Some,” blasting from the open doors of a huge four-wheel-drive truck. Two very attractive teenage girls stand on the truck’s roof, dancing to the music. Both are outfitted in tight, shimmering spandex pants, halter tops, and moon boots. They bump their perfectly shaped asses together and sing along with David Lee Roth: “Everybody wants some/I want some too/Everybody wants some, baby, how ’bout you.” As I walk by, a girl with feathered blond hair points at me and sneers, seductively, singing, “Everybody wants some, baby, how ’bout you?”

I do.

A week later, I end up ditching school with the monster truck’s down-jacket-wearing owner and the two dancing girls. We drive into the nearby mountains to sip Southern Comfort and smoke pot. The girls tell me that Van Halen singer David Lee Roth is a “super fox” and they both desperately want to fuck him. On the drive home, I’m in the truck’s back seat making out with the blond girl. Her lip gloss tastes like raspberry candy. I caress her nipples through her shirt and eventually slip a finger between her legs, which seems like a monumental achievement. I stop when I realize she has fallen asleep in my arms. A few days later, she pulls me into an unoccupied darkroom between classes and we fondle one another for a few seconds. After several more brief flirtations, the pull of our opposing camps is just too much and we eventually stop talking. A year later, I run into her at a local hamburger stand, where she works behind the counter. She hands me my food and waves me off before I can pay.

***

I’m an eighteen-year-old in the basement of a Hollywood nightclub called the Cathay De Grande. Slumped in an empty booth, my eyes are closed and my head rests on the table. Fifteen minutes earlier, I injected heroin inside the cramped restroom with the sound man. It is a Monday night and a local blues outfit called Top Jimmy and he Rhythm Pigs are on the small stage. They are fronted by a white-trash blues legend, Top Jimmy, and play the club every Monday night. The place is nearly empty. The Rhythm Pigs are cool, but like most in attendance, I am really here to score drugs. This accomplished, I nod off, lost in some distant dream world as the band plays their hearts out just a few feet away.

When I eventually drift back to reality, something odd catches my ear. Instead of Top Jimmy’s throaty voice, someone lets loose with an exaggerated, arena-rock scream. Perplexed, I lift my head and focus on the small stage. There, sandwiched between the band’s rotund bass player and slovenly guitar player, Carlos Guitarlos, is none other than David Lee Roth, holding the microphone and striking a majestic rock pose. It’s surreal seeing one of the most successful singers in the world standing in this dilapidated basement club alongside a bunch of musicians teetering on the brink of homelessness and liver failure.

“Whoa-bop-ditty-doobie-do-bop, oh yeah, baby!” Roth yells out, putting his arm around an inebriated Top Jimmy. As bleary-eyed Jimmy leans in and begins to sing, Roth watches him with a beaming smile, clapping his hands and laughing in exaggerated-but-sincere appreciation. “Top-motherfucking Jimmy!” he yells out, as if addressing a sold-out arena instead of several stunned junkies and alcoholics. The reaction from the sparse crowd is indifference bordering on hostility. There is nothing less cool in the Hollywood underground than a seemingly happy millionaire rock star. But Top Jimmy is smiling with his arm around Roth. And a few years later, when Van Halen releases its multiplatinum-selling record 1984, the album features a track called “Top Jimmy.”

“Top Jimmy cooks, Top Jimmy swings, Top Jimmy—he’s the king,” Roth sings in tribute to his friend, who would eventually die of liver failure.

***

The next two decades are a creative dark age for Van Halen. After years of ego-fueled turmoil from all sides, David Lee Roth leaves the band to pursue a doomed solo career. An entirely unremarkable singer named Sammy Hagar replaces him and Van Halen becomes one of the most boring bands in existence. Roth recedes from the limelight, studying martial arts and making an ill-fated stab as a radio deejay.

Eddie’s excessive drinking begins to take a toll. One night in 1993 at the height of the grunge years, a drunken Eddie appears backstage for a Nirvana concert at the Forum. He reportedly begs Kurt Cobain to let him join the band on stage, explaining, “I’m all washed up; you are what’s happening now.” He also, for unexplained reasons, supposedly sniffs Cobain’s deodorant before calling Nirvana’s half-black rhythm guitarist Pat Smear a “Mexican” and a “Raji.” Needless to say, he is not allowed on stage.

In the following years, news of Van Halen is sporadic, largely unsubstantiated, and generally not positive. One story has Eddie sitting in with guitarless rap-rock buttheads Limp Bizkit. When they are slow to return his prized equipment, Eddie supposedly goes back with automatic weapons. An acquaintance of mine who sells rare guitars does some business with Eddie and subsequently receives lonely, rambling, late-night phone calls from him. An old friend who is now a teacher hosts a day for his students to bring in their grandparents. One student inexplicably brings in Eddie Van Halen. He stays for hours, politely talking to the kids about his Dutch heritage and childhood music studies.

During this time, Roth is arrested in a New York City park for purchasing weed. And when a meth-addled man attempts a wee-hours break-in at the singer’s Pasadena mansion, the intruder is surprised to find “Diamond Dave” wide awake and at the ready. Some accounts have Roth training a gun on the intruder while others have the lifelong martial-arts enthusiast, resplendent in silk pajamas, subduing the man with a lightening-fast nunchuck demonstration.

But as the years pass, “important” bands like Nirvana feel increasingly dated while the celebratory party anthems of Roth-era Van Halen continue to dominate the airwaves. Their songs are played repeatedly every day on multiple stations throughout the civilized world. And after several well-publicized misfires including an aborted reunion and a stint with a much-maligned singer named Gary Cherone, Eddie Van Halen and David Lee Roth finally find their way back to each other in 2007. The group announces it will be hitting the road, though original bassist Michael Anthony is to be replaced by Eddie’s sixteen-year-old son, Wolfgang, who reportedly suggested the tour and persuaded his dad to reconcile with Roth. What ensues is the band’s highest-grossing tour to date.

I catch Van Halen’s show at the gleaming new Staples Center in downtown L.A., anticipating a heartfelt homecoming. Instead, I get a slick and entertaining professional rock show. There are no missteps, but little if anything seems spontaneous. Then, leading into the song “Ice Cream Man,” Roth stops and delivers a monologue. I later learn from watching videos online that it’s pretty much the same speech in every city. Still, it has particular significance in Los Angeles, mere miles from where it all started. “The suburbs, I come from the suburbs,” Roth says to the cheering crowd. “You know, where they tear out the trees and name streets after them. I live on Orange Grove—there’s no orange grove there; it’s just me. In fact, most of us in the band come from the suburbs and we used to play the backyard parties there. … I remember it like it was yesterday.”

***

Not long ago, I’m at my parents’ house in those very suburbs, visiting with my dad, who is slowly dying, his body wasting away. After leaving his house, I stop for gas. As I stand at the pump, a tall, disheveled man approaches me. He begins to ask for spare change, then stops and stares at me. After a moment, he says my name. I look back blankly and he awkwardly introduces himself. It turns out that we grew up together. The once-handsome and talented athlete has been drinking hard and using cocaine, and his life has unraveled in dramatic fashion. The last I’d heard, he was living behind a local bar in an abandoned camper shell but was asked to leave for having too many guests and making too much noise. I ask how he is and he just shakes his head. I take out my wallet and offer a twenty, which he refuses. I insist, and he eventually palms the bill and slides it into a pocket. After some strained small talk, he asks for a ride to a friend’s apartment. I reluctantly agree.

The two of us drive through the streets of our shared childhood in awkward silence. The orange groves have long since turned into a sprawl of tract housing and circuitous dead ends, both literal and figurative. I turn on the radio, scan stations, and eventually stop on Van Halen’s 1978 classic “Ain’t Talkin’ ’Bout Love.” I turn up the volume. After a few seconds, the propulsive guitar riff fades down and David Lee Roth begins to talk.

“I been to the edge, an’ there I stood an’ looked down/You know I lost a lot of friends there, baby, I got no time to mess around.”

The music builds in intensity before exploding into a powerful, defiant chorus: “Ain’t talkin’ ’bout love, my love is rotten to the core/Ain’t talkin’ ’bout love, just like I told you before, before, before/Hey hey hey!” By this time, my old friend is singing along and pumping his fist in the air. His eyes are moist from either alcohol, sadness, or both. The song finishes just as we pull in front of a dilapidated apartment complex, and he climbs out. He hesitates and looks in at me.

“Hey man, remember those crazy parties back in the day?” I nod and force a smile. Those were some good fucking times,” he says, reaching in and slapping my shoulder affectionately before disappearing into the darkness.

By John Albert

The first time I hear Van Halen I am fourteen years old, riding in a car through the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains. My friend Steve Darrow is riding shotgun while his dad steers the dusty old Volvo station wagon. Chris Darrow is in his forties and has long hair and a slightly drooping cowboy mustache. In the sixties and early seventies, as a member of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band and an obscure but influential group called the Kaleidoscope, he, along with Gram Parsons, Linda Ronstadt, and others, forged what became the classic California sound. His long-haired, Black Sabbath–loving son, Steve, sitting shotgun next to him, would go on to play in an early version of Guns N’ Roses. But on this particular night Chris is driving us and another friend named Peter home from a party thrown by a local ceramics artist. While the aging hippies and college professors sipped wine and purchased meticulously decorated casserole plates, my friends and I hiked into a nearby orange grove to smoke pot in the moonlight. And as the car heads home along Baseline Boulevard, passing the silhouttes of orange groves and vineyards, the three of us are still incredibly stoned and no one is talking much.

Someone turns on the radio. It’s tuned to KROQ, a small, independent station that has little in common with the corporate behemoth it would become. In 1978, the station broadcasts a strange mix of surreal sketch comedy and new music across the Southland. A show called The Hollywood Night Shift riffs on “barbecue bat burgers” and “downhill screen-door races.” Meanwhile, the station’s present-day last man standing, Rodney Bingenheimer, who morning goons Kevin and Bean use as a prop for their moronic shtick, introduces punk music to kids across Southern California. By this time, my friends and I have already fallen under the sway of the raw, new sounds emerging from a ripped, torn, and safety-pin-adorned England.

As we cruise along Baseline, I have no idea what’s on the radio. I stare out the window into a passing darkness with hazy, Mexican-weed-induced tunnel vision. Then, suddenly, this extraordinary sound from the car’s stereo snaps me back. Steve reaches over and turns up the volume. It’s guitar playing, but not like anything we have heard before. Until this very moment, the reigning guitar heroes have been English, amateur warlocks, such as Jimmy Page and Ritchie Blackmore, playing sped-up, bastardized versions of American blues. But this is faster and weirder. Toward the one-minute mark, the playing veers into completely uncharted territory, and the final forty-two seconds sound like Gypsy jazz legend Django Reinhardt on CIA acid.

It is a style of playing that will so dramatically alter the musical landscape that thirty years later it will sound normal, even rote. But in 1978, this burst of unabashed virtuosity and noise, something we’ll later learn is appropriately called “Eruption,” earns unexpected respect from three punk rock children and one middle-aged country rock musician. As the whole thing reaches a frenzied crescendo of undulating distortion, the four of us start to laugh.

Until, that is, the distortion immediately segues to a revamped version of the Kinks’ classic “You Really Got Me,” rumbling through the car’s little speakers. This is not hard rock as we know it—no highpitched, operatic wailing about sorcery or Viking lore. With no visual reference to go on, it seems to have as much in common with early punk as with bands such as Led Zeppelin and Rush—except, of course, for the crazy, outer-space guitar solo. In retrospect, this makes perfect sense. Before it became one of the biggest bands in the world, Van Halen routinely played on bills with prepunk bands like the Runaways, the Mumps, and the Dogs.

When the song ends, Steve’s dad, who may or may not be stoned as well, just nods his head and says, “Far out.”

***

It is the soundtrack to a world that doesn’t exist anymore. I know because that world is where I come from.

Van Halen had been playing the suburbs east of Los Angeles for several years before we heard them on the radio that night. In fact, the previous year, Peter’s diminutive, science-teacher mom, who when speaking tended to coo pleasantly like a pigeon, unwittingly supplied Van Halen with several bottles of bourbon and tequila. The occasion was the band’s appearance at a show on the local college radio station hosted by Peter’s older, but still underage, brother and some of his friends. Following seventies rock etiquette, they felt it only proper to provide the band with alcohol and other recreational substances.

I remember this because my friends and I had been coerced into distributing fliers announcing the band’s appearance on the show. Most of our peers glanced at the crudely rendered image of a young David Lee Roth flaunting his soon-to-be legendary chest pelt and bulging package and simply tossed the fliers away. A lot of those same kids would, several years later, pay large sums of money to see the band headline the massive Forum in Inglewood.

In the years leading up to their record deal and worldwide fame, the Internet was still science fiction and the only video game widely available, Pong, mimicked pingpong only without the riveting excitement and health benefits. As a result, kids were primarily focused on two things, rock music and getting wasted. Days were spent under the sun and smog, getting high, playing sports, skateboarding in empty swimming pools and on downhill streets. Weekend nights were devoted almost entirely to massive backyard parties. And Van Halen ruled the backyard party scene in and around the San Gabriel Valley.

Unsuspecting parents would leave town and hundreds of kids would descend on a designated home like tanned, stoned locusts. Down the block from my parents’ house was a large, ramshackle manor known as the Resort. Sunburned British drunks lived there, and their kids were a wild and eccentric brood bearing names such as Yo-Yo, Kiddy, Sissy, Lad, and Mims.

Parties at the Resort were notorious. I remember watching a formally attired adult couple slow their car in front of the Resort as a party raged inside. Some longhaired kids staggered into the street, walked onto the hood of the couple’s car and then its roof, howling like wolves. My preteen friends and I finally mustered the courage to venture inside one of the parties. There, we discovered a maze of hedonistic delights: the dining-room table lined with cocaine, a cracked door revealing a nubile high school girl having sex, people jumping from second-story windows into the pool, fights and noisy drag races in the street out front. Throughout the beautifully raucous affair, a young rock ’n’ roll band named China White stood precariously close to the swimming pool playing with all the swagger of the Rolling Stones at Madison Square Garden.

While Van Halen played the huge outdoor parties and lucrative high school dances, China White was the band of choice in my immediate neighborhood. The group was composed of young heroin addicts who wore cowboy hats and played Southern rock. Somehow, it was a style that made perfect sense in the slowed-down, drugged-out seventies suburbs. Besides a few performances at the Resort, the band’s highest-profile gigs were at the palatial hillside estate of a local ice cream fortune heir. The band’s leader, John Dooley, now lives in Bangkok, where he teaches music and plays in a rhythm and blues revue.

“Those were some epic fucking parties,” Dooley says when I reach him by phone in Bangkok. “We had a big stage on the tennis courts and the pool house was our backstage area. We invited 500 fellow students, charged a cover, and then got all my older brother’s biker buddies to bounce and run screen for the cops. There would be close to a thousand kids there and we would be getting high and fucking chicks in the pool house between sets. I remember we left with our guitar cases stuffed with cash.”

But it was with his next band, Mac Pinch, that Dooley’s path began to cross regularly with Van Halen’s as the two bands shared bills both locally and in Hollywood. “I was always really impressed by Eddie Van Halen and their bass player [Michael Anthony]. They definitely stood out musically, especially Eddie,” Dooley says. “Their singer, Roth, was like the guy we had—by no means a great singer, but really loud and worked the crowd well. They used to have a party van with the Van Halen logo painted on the sides, and Roth was always out there in that van. He was kind of obnoxious, but he had a real knack with the ladies. He would bring them out to that van one after another. I had more than my share, but Roth did better than his band and ours combined. We used to play this biker bar in Downey with them called the Downey Outhouse, where they served popcorn in bedpans and beer in urinals.

“It got pretty competitive between the bands, and one time our roadie unplugged Van Halen during a show at the Pasadena Civic.”

During these years, roughly 1974 to 1976, Van Halen surpassed all rivals, including San Fernando Valley stars Quiet Riot, to emerge as the premier hard-rock act in Los Angeles. Besides a willingness to play nearly anywhere at any time—the band once played an early-morning breakfast concert at my high school a few years before I attended—the band’s rise seemed due, largely, to two distinct qualities. One was the playing of Eddie Van Halen, who had perfected the innovative method of using the fingers of his picking hand to pound the guitar’s fret board, creating a lightning-fast, quasiclassical style that quickly became the talk of Southland musicians. Van Halen reportedly became so guarded about this technique that he began to play solos with his back to the audience.

And while the teenage boys came to marvel at Eddie’s technical virtuosity, the girls flocked to see the band’s flamboyant lead singer. David Lee Roth would take the stage shirtless, wearing skin-tight spandex pants or fur-lined assless chaps, none of which dampened his enthusiasm for jumping into the air and doing karate kicks and splits. Visually, Roth resembled a stoner superhero with his wild, long blond hair, muscular physique and exaggerated party bravado. But what set him apart from so many aspiring front men of the time, was that, unbeknownst to his mostly blond-haired, blue-eyed audience, Roth was Jewish. And though his father was a wealthy ophthalmologist, young Roth went to public schools and ended up attending primarily black John Muir High in Pasadena. As a result, he was able to merge an over-the-top, borscht-belt-like showmanship with the booty-shaking sex appeal of his Funkadelicized classmates. It was a combination that made Roth a near perfect rock star for those hedonistic times.

While Van Halen’s star rose, my friend Dooley and Mac Pinch were on a different trajectory. Instead of showcasing alongside their one-time rivals at Hollywood clubs such as the Starwood and the Whisky, the drug-addled young cowboys started booking USO tours and playing military bases to support their various nonmusical habits. When Van Halen finally had its big breakthrough and signed to Warner Bros. Records, Mac Pinch was off playing to halls of drunken Marines.

“Those were serious smack days for me,” Dooley reflects. “Eventually it all caught up to me and I had to come back home and do some jail time, and that was the end of the band.” (We don’t discuss how Dooley stole my parents’ television set.) I ask him if he has regrets after seeing his former rivals go on to such massive success.

“Do I think we should have tried harder? That maybe it could have been us?” he offers. “Sure. But we had a lot of fun playing those parties. I have some great memories. It was a pretty awesome time to be young and playing in a rock ’n’ roll band.”

***

Two years after first hearing Van Halen on the car radio, the world around me seems a dramatically different place. My once-long hair is now short and jagged and I’m wearing studded wristbands with a spider-shaped earring punched through an infected hole in my ear. In suburbs across Southern California, punk rockers have swelled from a besieged minority to an increasingly aggressive subculture. There are pervasive hostilities between the heavy-metal-loving “stoners” and the new punks. Both sides instigate violence. By now, I have been expelled from the local high school for truancy and am enrolled in something called Claremont Collegiate Academy. Despite its snooty name, the place is filled with kids who have failed at the local high schools. My classmates are mainly longhaired drug users, agitated Iranian immigrants, and kids with assorted behavioral disorders. The principal will eventually be arrested on child porn charges.

During one lunch break, I stroll out into the school parking lot and am greeted by the pounding, tribal drums of Van Halen’s latest single, “Everybody Wants Some,” blasting from the open doors of a huge four-wheel-drive truck. Two very attractive teenage girls stand on the truck’s roof, dancing to the music. Both are outfitted in tight, shimmering spandex pants, halter tops, and moon boots. They bump their perfectly shaped asses together and sing along with David Lee Roth: “Everybody wants some/I want some too/Everybody wants some, baby, how ’bout you.” As I walk by, a girl with feathered blond hair points at me and sneers, seductively, singing, “Everybody wants some, baby, how ’bout you?”

I do.

A week later, I end up ditching school with the monster truck’s down-jacket-wearing owner and the two dancing girls. We drive into the nearby mountains to sip Southern Comfort and smoke pot. The girls tell me that Van Halen singer David Lee Roth is a “super fox” and they both desperately want to fuck him. On the drive home, I’m in the truck’s back seat making out with the blond girl. Her lip gloss tastes like raspberry candy. I caress her nipples through her shirt and eventually slip a finger between her legs, which seems like a monumental achievement. I stop when I realize she has fallen asleep in my arms. A few days later, she pulls me into an unoccupied darkroom between classes and we fondle one another for a few seconds. After several more brief flirtations, the pull of our opposing camps is just too much and we eventually stop talking. A year later, I run into her at a local hamburger stand, where she works behind the counter. She hands me my food and waves me off before I can pay.

***

I’m an eighteen-year-old in the basement of a Hollywood nightclub called the Cathay De Grande. Slumped in an empty booth, my eyes are closed and my head rests on the table. Fifteen minutes earlier, I injected heroin inside the cramped restroom with the sound man. It is a Monday night and a local blues outfit called Top Jimmy and he Rhythm Pigs are on the small stage. They are fronted by a white-trash blues legend, Top Jimmy, and play the club every Monday night. The place is nearly empty. The Rhythm Pigs are cool, but like most in attendance, I am really here to score drugs. This accomplished, I nod off, lost in some distant dream world as the band plays their hearts out just a few feet away.

When I eventually drift back to reality, something odd catches my ear. Instead of Top Jimmy’s throaty voice, someone lets loose with an exaggerated, arena-rock scream. Perplexed, I lift my head and focus on the small stage. There, sandwiched between the band’s rotund bass player and slovenly guitar player, Carlos Guitarlos, is none other than David Lee Roth, holding the microphone and striking a majestic rock pose. It’s surreal seeing one of the most successful singers in the world standing in this dilapidated basement club alongside a bunch of musicians teetering on the brink of homelessness and liver failure.

“Whoa-bop-ditty-doobie-do-bop, oh yeah, baby!” Roth yells out, putting his arm around an inebriated Top Jimmy. As bleary-eyed Jimmy leans in and begins to sing, Roth watches him with a beaming smile, clapping his hands and laughing in exaggerated-but-sincere appreciation. “Top-motherfucking Jimmy!” he yells out, as if addressing a sold-out arena instead of several stunned junkies and alcoholics. The reaction from the sparse crowd is indifference bordering on hostility. There is nothing less cool in the Hollywood underground than a seemingly happy millionaire rock star. But Top Jimmy is smiling with his arm around Roth. And a few years later, when Van Halen releases its multiplatinum-selling record 1984, the album features a track called “Top Jimmy.”

“Top Jimmy cooks, Top Jimmy swings, Top Jimmy—he’s the king,” Roth sings in tribute to his friend, who would eventually die of liver failure.

***

The next two decades are a creative dark age for Van Halen. After years of ego-fueled turmoil from all sides, David Lee Roth leaves the band to pursue a doomed solo career. An entirely unremarkable singer named Sammy Hagar replaces him and Van Halen becomes one of the most boring bands in existence. Roth recedes from the limelight, studying martial arts and making an ill-fated stab as a radio deejay.

Eddie’s excessive drinking begins to take a toll. One night in 1993 at the height of the grunge years, a drunken Eddie appears backstage for a Nirvana concert at the Forum. He reportedly begs Kurt Cobain to let him join the band on stage, explaining, “I’m all washed up; you are what’s happening now.” He also, for unexplained reasons, supposedly sniffs Cobain’s deodorant before calling Nirvana’s half-black rhythm guitarist Pat Smear a “Mexican” and a “Raji.” Needless to say, he is not allowed on stage.

In the following years, news of Van Halen is sporadic, largely unsubstantiated, and generally not positive. One story has Eddie sitting in with guitarless rap-rock buttheads Limp Bizkit. When they are slow to return his prized equipment, Eddie supposedly goes back with automatic weapons. An acquaintance of mine who sells rare guitars does some business with Eddie and subsequently receives lonely, rambling, late-night phone calls from him. An old friend who is now a teacher hosts a day for his students to bring in their grandparents. One student inexplicably brings in Eddie Van Halen. He stays for hours, politely talking to the kids about his Dutch heritage and childhood music studies.

During this time, Roth is arrested in a New York City park for purchasing weed. And when a meth-addled man attempts a wee-hours break-in at the singer’s Pasadena mansion, the intruder is surprised to find “Diamond Dave” wide awake and at the ready. Some accounts have Roth training a gun on the intruder while others have the lifelong martial-arts enthusiast, resplendent in silk pajamas, subduing the man with a lightening-fast nunchuck demonstration.

But as the years pass, “important” bands like Nirvana feel increasingly dated while the celebratory party anthems of Roth-era Van Halen continue to dominate the airwaves. Their songs are played repeatedly every day on multiple stations throughout the civilized world. And after several well-publicized misfires including an aborted reunion and a stint with a much-maligned singer named Gary Cherone, Eddie Van Halen and David Lee Roth finally find their way back to each other in 2007. The group announces it will be hitting the road, though original bassist Michael Anthony is to be replaced by Eddie’s sixteen-year-old son, Wolfgang, who reportedly suggested the tour and persuaded his dad to reconcile with Roth. What ensues is the band’s highest-grossing tour to date.

I catch Van Halen’s show at the gleaming new Staples Center in downtown L.A., anticipating a heartfelt homecoming. Instead, I get a slick and entertaining professional rock show. There are no missteps, but little if anything seems spontaneous. Then, leading into the song “Ice Cream Man,” Roth stops and delivers a monologue. I later learn from watching videos online that it’s pretty much the same speech in every city. Still, it has particular significance in Los Angeles, mere miles from where it all started. “The suburbs, I come from the suburbs,” Roth says to the cheering crowd. “You know, where they tear out the trees and name streets after them. I live on Orange Grove—there’s no orange grove there; it’s just me. In fact, most of us in the band come from the suburbs and we used to play the backyard parties there. … I remember it like it was yesterday.”

***

Not long ago, I’m at my parents’ house in those very suburbs, visiting with my dad, who is slowly dying, his body wasting away. After leaving his house, I stop for gas. As I stand at the pump, a tall, disheveled man approaches me. He begins to ask for spare change, then stops and stares at me. After a moment, he says my name. I look back blankly and he awkwardly introduces himself. It turns out that we grew up together. The once-handsome and talented athlete has been drinking hard and using cocaine, and his life has unraveled in dramatic fashion. The last I’d heard, he was living behind a local bar in an abandoned camper shell but was asked to leave for having too many guests and making too much noise. I ask how he is and he just shakes his head. I take out my wallet and offer a twenty, which he refuses. I insist, and he eventually palms the bill and slides it into a pocket. After some strained small talk, he asks for a ride to a friend’s apartment. I reluctantly agree.

The two of us drive through the streets of our shared childhood in awkward silence. The orange groves have long since turned into a sprawl of tract housing and circuitous dead ends, both literal and figurative. I turn on the radio, scan stations, and eventually stop on Van Halen’s 1978 classic “Ain’t Talkin’ ’Bout Love.” I turn up the volume. After a few seconds, the propulsive guitar riff fades down and David Lee Roth begins to talk.

“I been to the edge, an’ there I stood an’ looked down/You know I lost a lot of friends there, baby, I got no time to mess around.”

The music builds in intensity before exploding into a powerful, defiant chorus: “Ain’t talkin’ ’bout love, my love is rotten to the core/Ain’t talkin’ ’bout love, just like I told you before, before, before/Hey hey hey!” By this time, my old friend is singing along and pumping his fist in the air. His eyes are moist from either alcohol, sadness, or both. The song finishes just as we pull in front of a dilapidated apartment complex, and he climbs out. He hesitates and looks in at me.

“Hey man, remember those crazy parties back in the day?” I nod and force a smile. Those were some good fucking times,” he says, reaching in and slapping my shoulder affectionately before disappearing into the darkness.

No comments:

Post a Comment