Tuesday, 14 June 2011

From Guardian.co.uk:

Van Halen invent hair metal

Van Halen invent hair metal

May 1976: Number 32 in our series of the 50 key events in the history of rock music

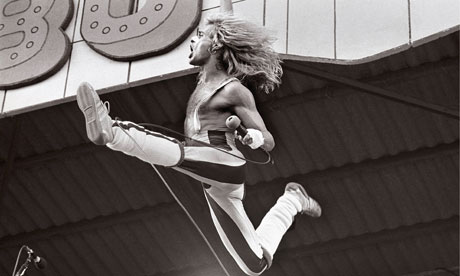

David Lee Roth, of Van Halen, performing live onstage. Photograph: Rob Verhorst/Redferns

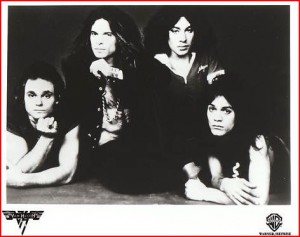

Thirty-five years ago, a four-piece American guitar band set about changing rock music for ever. They took their name from a brotherly relationship; they had a goofy, Jewish singer with family connections to New York bohemia; they added pop hooks and smarts to fast, aggressive guitar music; their debut album included a song with the word “punk” in its title; and they weren’t the Ramones.

Of course, you wouldn’t believe Van Halen were the most important American band of the late 70s if you only read rock critics. They were too popular, too vulgar, too much, too soon. They celebrated idiocy. So did the Ramones, of course, but Van Halen’s idiocy was of a different order to punk’s: it wasn’t built around comic-book humour, but on David Lee Roth’s apparent range of interests, which ran the gamut of pursuits from casual sex to casual intoxication, with nothing in between. The tension between Roth’s goofiness and stellar guitarist Eddie van Halen’s desire to be taken seriously was at the heart of their music, and eventually tore the pair apart.

Van Halen, legend holds, were spotted by Gene Simmons of Kiss, playing at the Starwood club in Los Angeles in 1976. Simmons was so impressed he flew the band to New York to produce a session for them at his own expense. All the elements that instantly identify Van Halen were present on the Simmons demos: it’s no wonder that when they came to record their official debut, it took just days, with minimal overdubbing. Roth was already a blowhard, Eddie’s guitar technique was clearly light years ahead of the competition, Alex Van Halen and Michael Anthony were a thunderous rhythm section.

Their signature sound was clean, precise and full of attack: there’s absolutely no fat on the songs that made their name. Where heavy rock’s use of the blues had previously been trudging and unwieldy, Van Halen added a sense of flight, taking away the swing, speeding even a simple 12-bar into something entirely unrelated to its source. They closed their debut album with a version of John Brim’s old blues Ice Cream Man, and even then you can’t imagine, say, Humble Pie coming up with such a confection.

That debut was nothing short of a paradigm shift in the sound of heavy music, as important as Jimi Hendrix’s first record had been a decade before, and Nirvana’s second would be in closing the era Van Halen began. It sounded like nothing before it, yet also like it could have been made at any time until Nevermind was released 13 years later: that’s an awfully long time to sound undated. But the bands Van Halen spawned, sadly, were pallid imitators without Van Halen’s invention and skill. Van Halen had transformed rock by unwittingly creating music’s most profitable rubbish dump.

The difference between Van Halen and the hair metallers who followed was what always separates game-changers from imitators: their wide listening habits. In his first big interview, Eddie Van Halen explained: “Dave our singer doesn’t even own a stereo. He listens to the radio, which is a good variety … Most of our songs you can sing along with, even though it does have the peculiar guitar and end-of-the-world drums.”

Not that Roth cared about being refracted through hair metal. In fact, he boasted, that wasn’t the real extent of Van Halen’s influence. As he told the writer Lisa Robinson in 1984, at the peak of the band’s powers: “I know for a fact that to a small degree, we’ve bred a small legion of imitators, copycats, mimics, people who are using Van Halen for their sole inspiration. But even more important than that are all the people who are just disgusted and revolted by our music and our presence and our appearance and the way I do interviews, and they’ve been forced to come up with some very substantial musical alternatives to Van Halen-type rock, and that’s why we have new wave.”

That interview shows a fascinating man toying with his interrogator. Roth references John Cassavetes and George Bernard Shaw, but still pins down what Van Halen really meant: “I would still prefer to think of us as witless and tasteless. Arch enemy of the common public. That’s all I wanted to be in life, really. I always wanted to be an outrage to public decency and a threat to women. And this is one of the few occupations where you’re not only allowed that, but you’re encouraged.”

Of course, you wouldn’t believe Van Halen were the most important American band of the late 70s if you only read rock critics. They were too popular, too vulgar, too much, too soon. They celebrated idiocy. So did the Ramones, of course, but Van Halen’s idiocy was of a different order to punk’s: it wasn’t built around comic-book humour, but on David Lee Roth’s apparent range of interests, which ran the gamut of pursuits from casual sex to casual intoxication, with nothing in between. The tension between Roth’s goofiness and stellar guitarist Eddie van Halen’s desire to be taken seriously was at the heart of their music, and eventually tore the pair apart.

Van Halen, legend holds, were spotted by Gene Simmons of Kiss, playing at the Starwood club in Los Angeles in 1976. Simmons was so impressed he flew the band to New York to produce a session for them at his own expense. All the elements that instantly identify Van Halen were present on the Simmons demos: it’s no wonder that when they came to record their official debut, it took just days, with minimal overdubbing. Roth was already a blowhard, Eddie’s guitar technique was clearly light years ahead of the competition, Alex Van Halen and Michael Anthony were a thunderous rhythm section.

Their signature sound was clean, precise and full of attack: there’s absolutely no fat on the songs that made their name. Where heavy rock’s use of the blues had previously been trudging and unwieldy, Van Halen added a sense of flight, taking away the swing, speeding even a simple 12-bar into something entirely unrelated to its source. They closed their debut album with a version of John Brim’s old blues Ice Cream Man, and even then you can’t imagine, say, Humble Pie coming up with such a confection.

That debut was nothing short of a paradigm shift in the sound of heavy music, as important as Jimi Hendrix’s first record had been a decade before, and Nirvana’s second would be in closing the era Van Halen began. It sounded like nothing before it, yet also like it could have been made at any time until Nevermind was released 13 years later: that’s an awfully long time to sound undated. But the bands Van Halen spawned, sadly, were pallid imitators without Van Halen’s invention and skill. Van Halen had transformed rock by unwittingly creating music’s most profitable rubbish dump.

The difference between Van Halen and the hair metallers who followed was what always separates game-changers from imitators: their wide listening habits. In his first big interview, Eddie Van Halen explained: “Dave our singer doesn’t even own a stereo. He listens to the radio, which is a good variety … Most of our songs you can sing along with, even though it does have the peculiar guitar and end-of-the-world drums.”

Not that Roth cared about being refracted through hair metal. In fact, he boasted, that wasn’t the real extent of Van Halen’s influence. As he told the writer Lisa Robinson in 1984, at the peak of the band’s powers: “I know for a fact that to a small degree, we’ve bred a small legion of imitators, copycats, mimics, people who are using Van Halen for their sole inspiration. But even more important than that are all the people who are just disgusted and revolted by our music and our presence and our appearance and the way I do interviews, and they’ve been forced to come up with some very substantial musical alternatives to Van Halen-type rock, and that’s why we have new wave.”

That interview shows a fascinating man toying with his interrogator. Roth references John Cassavetes and George Bernard Shaw, but still pins down what Van Halen really meant: “I would still prefer to think of us as witless and tasteless. Arch enemy of the common public. That’s all I wanted to be in life, really. I always wanted to be an outrage to public decency and a threat to women. And this is one of the few occupations where you’re not only allowed that, but you’re encouraged.”

Guns N' Roses

Guns N' Roses  Tommy Lee raises a glass to single releases

Tommy Lee raises a glass to single releases

In fact, the document is so brimming with jokes, insults, useless facts, self-deprecation, and pop culture references that TSG will devote a second story to those highlights. This dispatch will focus on

In fact, the document is so brimming with jokes, insults, useless facts, self-deprecation, and pop culture references that TSG will devote a second story to those highlights. This dispatch will focus on

Work starts July

Work starts July

Ozzy Osbourne had a pair of unlikely guest vocalists on his 1988 album No Rest for The Wicked: Howard Kaylan and Mark Volman, better known as Flo and Eddie from Frank Zappa's Mothers of Invention and The Turtles (of “Happy Together” fame). In the second part of his long-ranging interview with Bravewords.com, bass player Bob Daisley said Flo and Eddie sang background vocals on the album, for which Daisley wrote the lyrics. No Rest was Ozzy's first album with Zakk Wylde on guitar.

Ozzy Osbourne had a pair of unlikely guest vocalists on his 1988 album No Rest for The Wicked: Howard Kaylan and Mark Volman, better known as Flo and Eddie from Frank Zappa's Mothers of Invention and The Turtles (of “Happy Together” fame). In the second part of his long-ranging interview with Bravewords.com, bass player Bob Daisley said Flo and Eddie sang background vocals on the album, for which Daisley wrote the lyrics. No Rest was Ozzy's first album with Zakk Wylde on guitar.